Le Monde illustré. 1871-04-08 (Source: gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France)

April 1871, the Paris Commune, “a new power that was truly democratic” (Engels, MEW 22/198), is in full swing, and the feminist Marxist communard, Élisabeth Dmitrieff, enthusiastically declares: “We lift up all the women of Paris” (Dmitrieff 1871, 36). One of the first large-scale feminist movements organised around class struggle had been born. The anti-communards do not hesitate to give this new phenomenon a name: “Pétroleuses. A hideous word, that was not yet in the dictionary: but unknown horrors necessitate gruesome neologisms” (Gautier 1872, 21). Karl Marx will contradict and praise, with no reservations, the courage of these women who, “joyfully give up their lives at the barricades and on the place of execution” (MEW 17/357).

Since the Napoleonic Code, women were completely excluded from the French public sphere. In March 1871, however, the women surrounded the national guard and on 14 April 1871, 10,000 were at the barricades. Active in a number of mixed committees, they organised 160 women’s clubs. Among them, The Women’s Union for the Defence of Paris, tied to the French female section in the First International, organised 24 public meetings in one month, among which 4,000 women participants were included. Based on Marx and Engels’s analysis, they “recruit new activists from a clearly proletarian milieu” (Thomas [1963] 2019, 117), propelling the internationalisation of women’s struggles.

If communard women come from diverse backgrounds and form a “complex subject” (Schulkind 1985), they converge in their admiration for the revolutionary women fallen in 1789, 1830, and 1848. They also stand out. Based on these past experiences, they agree that struggles oriented towards an extension of the liberal legal and political apparatus (Nikell/ Haug 1999) are not enough. They centre their project, instead, on the idea that the “unity which has been imposed on us until this day by empire, the monarchy, and parliamentarism, is a despotic, unintelligent, arbitrary, or onerous centralisation […]. Those that lead an engaged struggle cannot end it through delusory compromises; the outcome cannot be doubted” (Programme, 19.04.1871, p. 194).

Women’s liberation is no longer fathomable without the emancipation of the proletariat and the class struggle, which determine their destiny from that moment on. (Bergmann 1995). The Appeal to the Citizens of Paris launched by the communard women is explicit. “Our enemies are those that the current social order privileges, all those who profit off of our sweat, who have grown fat off of our misery. We want work to reap its profits; no more exploiters and masters”. It is the first time in the history of European feminisms that a mass movement of women rallies under this slogan. As the feminist communard André Léo states, “the only path is to come together for common action under the same banner” (La République des travailleurs, 10.01.1871, 1).

Far from limiting their space of action, women have, for the first time in France, political responsibilities. Unprecedented measures are taken which profoundly “challenge the dominant gender ideologies and practices” (Eichner 2004, 2). Buried by the ensuing repression, these measures will not materialise until much later on. Others have yet to be put into practice. The right to divorce by mutual decision, the recognition of free marital unions and of all children out of wedlock, the abolition of all the economic competition between the sexes, the demand for equal pay, the creation of public nurseries, provision of education for all, and the fusion of male and female education – only put into effect in the 1970s – were part of this project.

The figure of the pétroleuses emerges as a response to this process. This word creation designates all who have “denied the immense and glorious role of woman in society” (Audiences on 4 and 5 September, 1871), and marks the convergence of class hatred and disgust of proletarian women. Conservatives accuse them of having transformed a central element of their domesticity — petroleum [heating fuel] — as a destructive instrument of the nuclear family, the backbone of class society. Fashioned out of thin air, the tale of the pétroleuses is nonetheless one of the most powerful anti-revolutionary political constructions from the end of the 19th cent., helping create the “imaginary of the Commune” (Ross 2015).

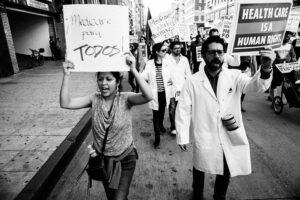

Constructed to ridicule the collective action of women, it redraws the memory of the revolutionary process by inverting its historical significance. The creation of an egalitarian societal alternative is transformed into a phenomenon of pure destruction, where the madness of the poor and female hysteria combine. Misleading photomontages, caricatures in the press and false accounts are unleashed in order to transform communard women into pétroleuses — a mixture of sorcerer and prostitute, “an obscene hydra, sadistic, hysteric and cruel” (Lidsky 2010, 112), denying, through these images, the full scope of their political project.

The myth is denied by the survivors of the commune, who immediately denounce it. Yet, the massacre gives way to the history told by the victors. The following decades are marked by a shroud of silence and the treatment of communard men and women as pariahs, the consequence of which do not spare the French feminist movement. Its liberal tendency, in republican form, is predominant at the end of the 19th cent. It focuses its scope of action largely on the question of suffrage and does not question the existing social order. In these spaces, communard women, murdered, exiled, or imprisoned, are hardly represented at the height of their accomplishments, leaving room for large silences concerning their past victories.

But the history of the defeated communards was recounted by the defeated themselves (Haug 1997). In 1882, The Association of Friends of the Paris Commune was created. From the beginning of the 20th cent., the commune is commemorated by communists, socialists, and anarchists alike as the “glorious anniversary of the concept of feminism” (Biais 1901). The myth of the pétroleuses continues to be denounced and the transmission of memory carries on in activist spaces.

In the 1930s, for the first time, a change in the meaning of the word occurs. French communist women appropriate it explicitly in 1933. “Let us follow the example of the pétroleuses of 1871” (L’Humanité, 28.06.1933). As fascism gains strength and the French feminist movement becomes more and more conservative, they subvert the negativity in the expression and offer the pétroleuse her first positive appropriation. It henceforth became a synonym for resistance in the face of state violence.

The Resistance crystallises this positive connotation. In 1963, Édith Thomas, a communist activist, member of the Resistance and pioneer of women’s history, embarks on the construction of a history of revolutionary women, a memory work that she deems essential. She publishes the first significant work on the communard women, entitled Pétroleuses (1963). The appropriation of the term consecrates, at the same time, the plurality of the movement, its transgressive character in the face of established power and its combination of anti-capitalist and feminist struggle.

The term is taken up again in 1968, imbued with its historical dimension. “The Pétroleuses: a publication of women who struggle,” is a case in point. This feminist current chooses the historical affiliation with the pétroleuses to posit anti-capitalist struggle at the core of its feminist project, consolidating the revolutionary meaning of the term. The pétroleuses line celebrates its centennial.

Nowadays, the meaning does not seem to evolve anymore, bur nor does it appear at the forefront of debate with the same intensity. In general terms, women’s and gender history at the turn of the 21st cent have often narrowly defined feminist struggles as synonymous with the efforts of women to “the fight for citizenship and suffrage” (Vergès and Jones 1991, 492). As a result, the history of the women of the Commune and their feminist achievements “has been marginalized” (492) in feminist historiography.

“Forgotten by history” (Rey 2018), it was only in 2012 that the Women’s Union for the Defense of Paris [L’Union des femmes pour la défense de Paris] was publicly recognised as the first large-scale feminist organisation in France. The connection between Marx and Engels’s thinking and the achievements of this movement merit, in turn, further exploration (Haug 2001).

Communard women did not use the term feminism in order to define themselves. In their time, “it designated solely the struggle for an expansion of individual rights within the boundaries of liberal society” (Bonnet/Neves 2021). Their engagement was for the creation of another societal form; with it, they also inaugurated another tradition of women’s emancipation and a new meaning for feminist struggle.

Annabelle Bonnet

Translated by Vanessa Gravenor

The author thanks the Association “Les Amies et Amis de la Commune de Paris” (https://www.commune1871.org)

Bibliography

M. Biais, “Le féminisme de la Commune,” La Fronde, 19.03.1901

A. Bonnet et V. Neves, “As mulheres na Comuna de Paris,” A Terra é redonda, 2021

“Commune de Paris. Programme, 19.04.1871,” Annales de l’Assemblée nationale : Compte rendu in extenso des séances, Volume 10, Assemblée nationale (1871-1942), La Commune, 1871

É. Dmitrieff, “É. Dmitrieff à H. Jung” Lettres de communards et de militants de la Ire Internationale à Marx (…), Paris 1934

C. Eichner, Surmounting the barricades : women in the Paris Commune, Bloomington (Indiana)2004

K. Jones, et F. Vergès, “Women of the Paris Commune of 1871,” Women’s Studies Int. Forum, v. 14/5, 1991

“Les agents de la commune, les femmes incendiaires, Audiences des 4 et 5 septembre,” Le dossier de la commune devant les conseils de guerre, Paris 1871

F. Engels in K. Marx, The Civil War in France, New York [1871] 1940

“Notre programme,” La République des travailleurs, 10.01.1871

P. Lidsky, Les écrivains contre la commune, Paris [1970] 2010

C. Rey, A. Limoge-Gayat, S. Pépino, Petit dictionnaire des femmes de la Commune de Paris 1871: les oubliées de l’histoire, Paris 2018

K. Ross, Communal Luxury : the political Imaginary of the Paris Commune, London 2015

E. Schulkind, “Socialist women during the 1871 Paris Commune”, In : Past & Present, v. 106, Issue 1, Feb. 1985, p. 124-163

É. Thomas, Les pétroleuses, Paris [1963] 2019

Th. Gautier, Tableaux du siège. Paris 1870-1871, Paris 1872